Human Behavior Patterns

This project aims to model general human behavior patterns. This modeling of human behavior is meant to be descriptive, rather than prescriptive. Furthermore we aim to integrate state-of-the-art Artificial Intelligence concepts into into modeling human behavior patterns, notably from multi agent reinforcement learning (MARL).

What is human behavior?

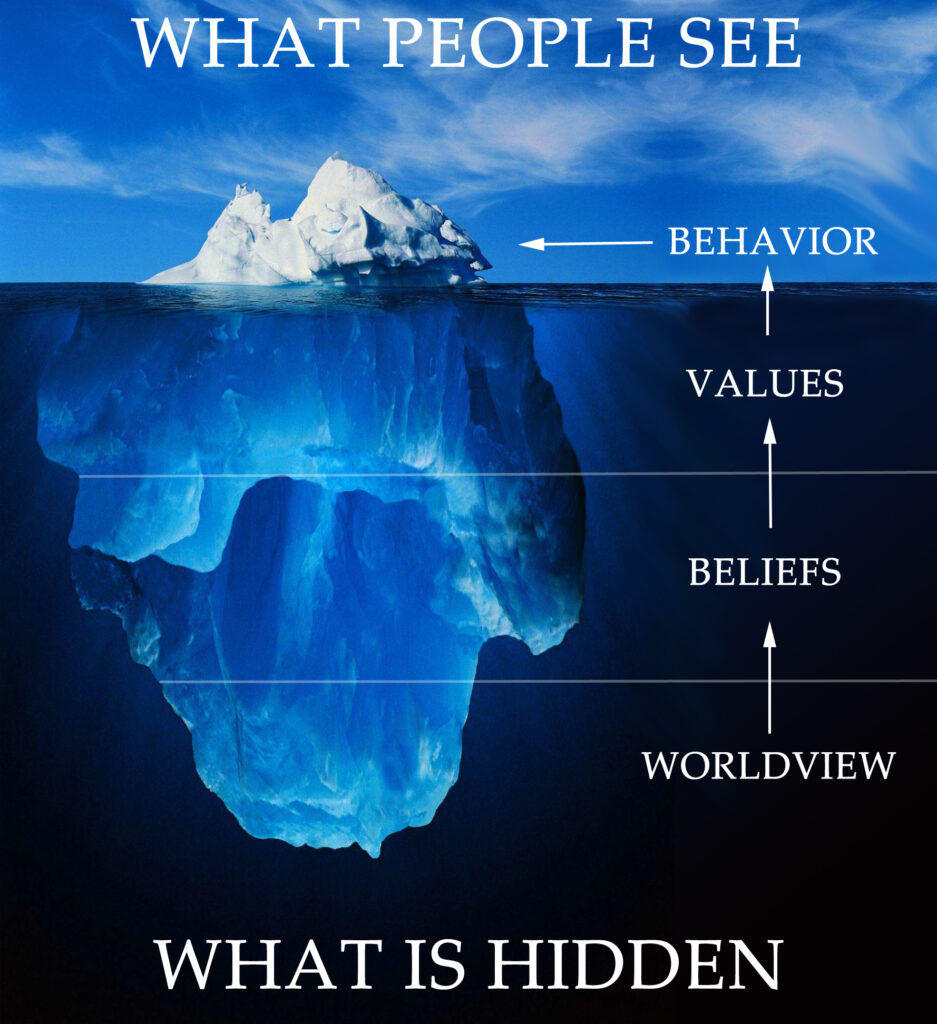

Human behavior encompasses the spectrum of actions and mannerisms exhibited by individuals within specific environments. It represents how individuals react to various stimuli or inputs, which can be internal or external, conscious or subconscious, overt or covert, and voluntary or involuntary. Typically, the term “behavior” is used to refer to the array of responses that can be observed by others, as exemplified in Display 1. However, the term human behavior in that perspective is subjective as for instance also brain waves can be detected by other people using specialized medical instruments. Therefore, we use the term of human behavior as as human responses which can be detected by the natural senses humans encompasses. In that respect we like to define behaviors which are somehow naturally visible to others, which is metaphorically depicted in Display 1.

Fundamentals – Which fundamentals do generate human behavior?

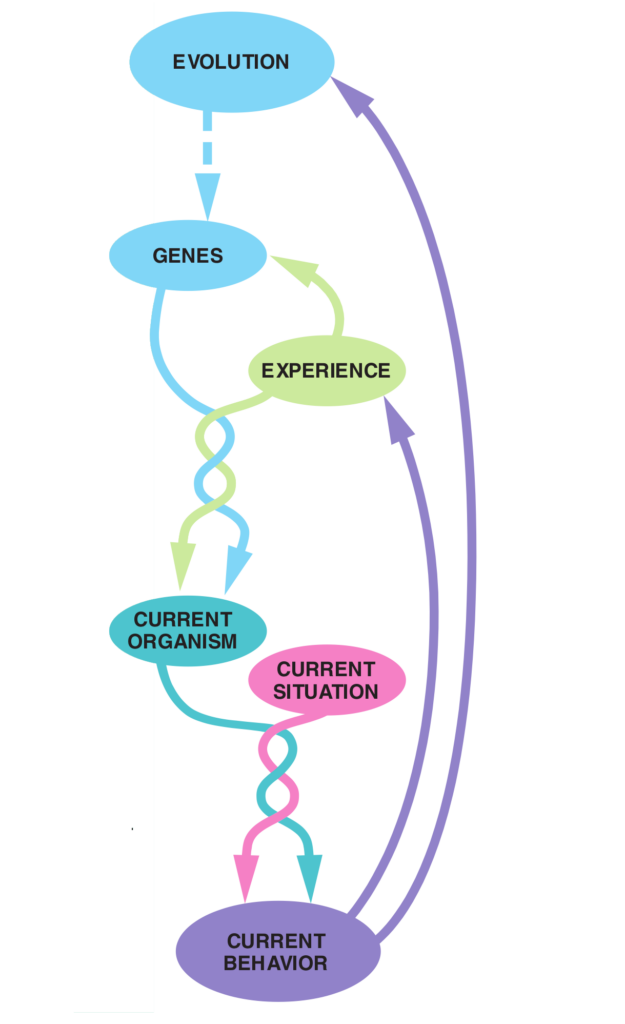

Despite the visibility of behavior, the origins or fundamentals of behavior are frequently not (or only partially) detectable by others, such as emotions, beliefs and intentions. In its most simplified form human behavior originates from a mixture of genetics (‘nature’) and experience (‘nurture’) which both intertwine and have feedback loops to (life time) experience and evolution, as shown in Display 2.

Evolution influences the pool of behavior-influencing genes available to the members of human beings. Experience modifies the expression of an individual’s genetic program. Each individual’s genes initiate a unique program of neural development. The development of an individual’s nervous system depends on its interactions with its environment (i.e., on its experience). Each individual’s current behavioral capacities and tendencies are determined by its unique patterns of neural activity, some of which are experienced as thoughts, feelings, memories, etc. The individual’s actual behavior arises out of interactions among its ongoing patterns of neural activity and its perception of the current situation. The success of each individual’s behavior influences the likelihood that its genes will be passed on to perpetuating offspring and thus influences evolution.

Human behavior could be viewed as contemporary action based upon ancestral hardware. Moreover, the origins of current human behavior is a blend of events in history ranging from millions of years in the past until split seconds ago, as shown in Display 3.

The dissection of the past is somewhat arbitrary: one could for instance also split the origins of behavior simply into ‘Nature’ and ‘Nurture’. Whatever the classification, the underlying components are also related to each other and are not strictly bounded.

The intention of this display however, is mainly to show that there is a range of determinants of human behavior originating from a long range of time.

What is the purpose of human behavior?

The purpose of human behavior is to make alterations to the environment which are beneficial to its individual well being. Individual well being of humans can also be enhanced by increasing the well being of other living organisms, notably other humans or relatives. All human behavior can be regarded as an investment with an uncertain payoff. Humans make consciously or unconsciously predictions of these probabilities in weighing alternative behavior options before executing them. In line with this investment analogy, humans naturally strive for some optimal payoff with minimal investment. In other words, humans aim for behaviors which generate maximal output with minimal input. This originates from natural selection which favors maximizing evolutionary fitness.

The brain and behavior – How does it work?

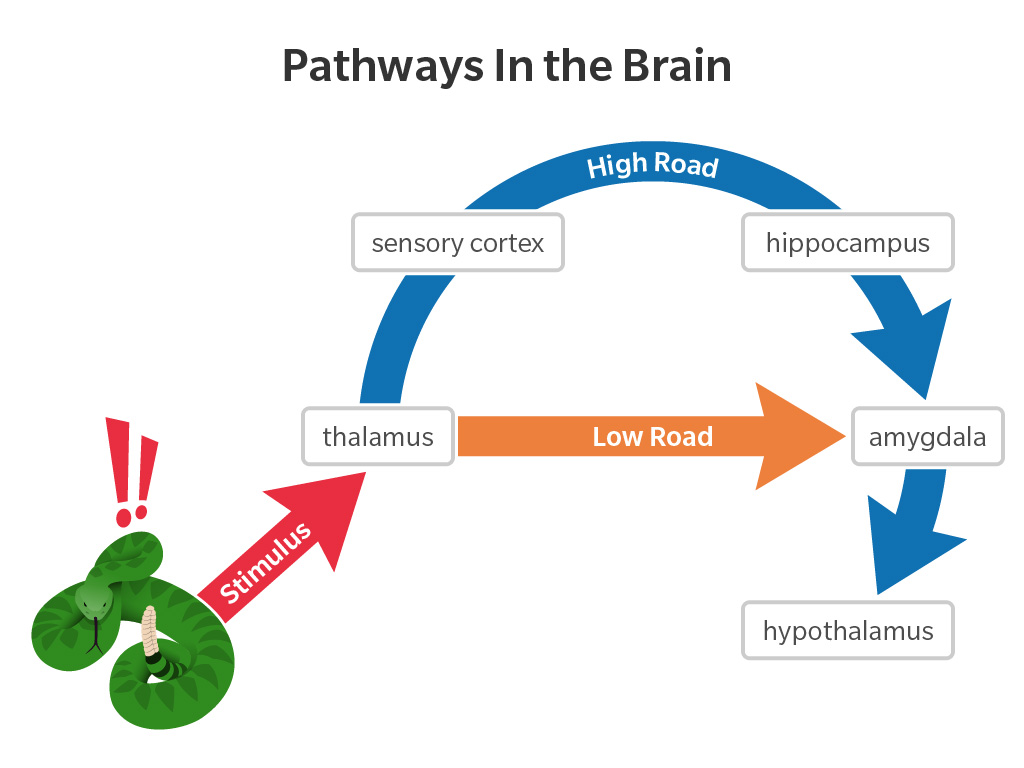

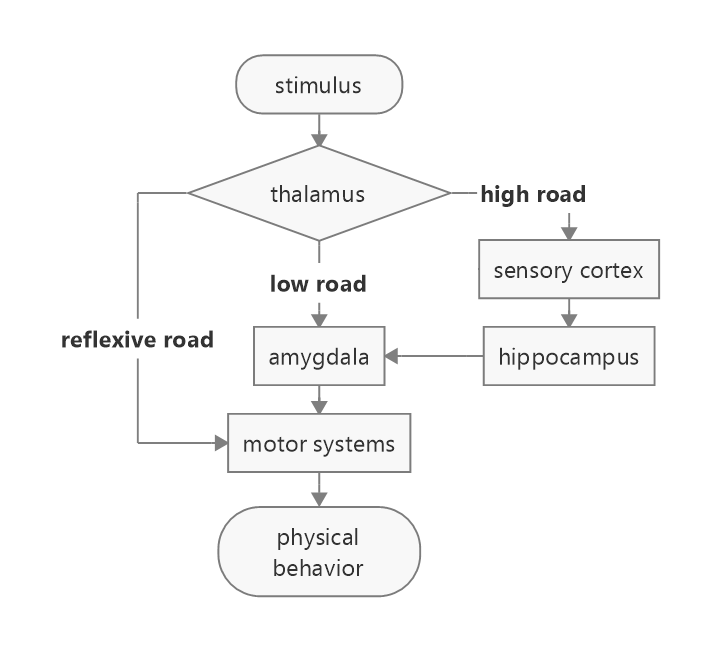

Humans can process stimuli from the environment which lead to behavior in various and very complex manners. Generally speaking there are three distinct pathways in the brain which are utilized in generating behavioral responses from external or internal stimuli:

- Reflexive (“automatic”)response

- Low road (“emotional”) response

- High road (“reflective”) response

A “low road response” and a “reflexive response” share similarities in terms of their quick and automatic nature but are not exactly the same.

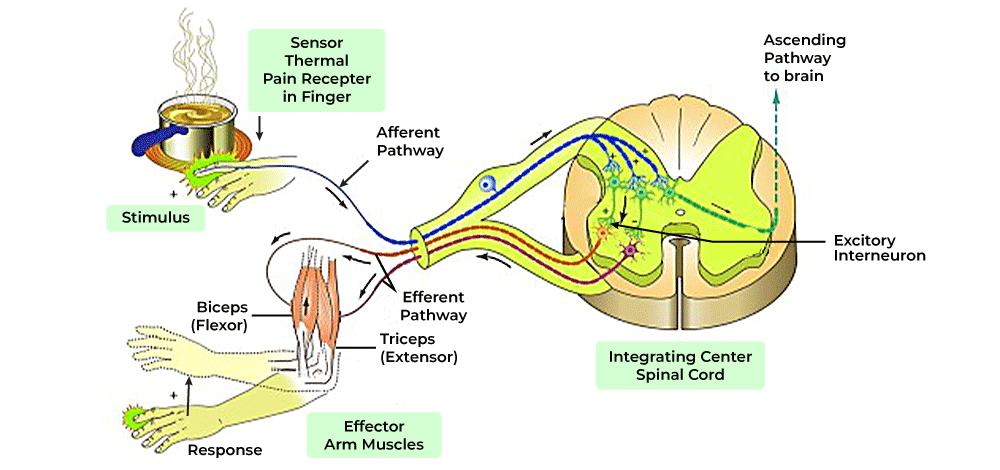

- Reflexive response: Reflexes are rapid, involuntary responses to a specific stimulus. They are typically controlled by the spinal cord or lower brain centers, bypassing conscious thought and emotions. A classic example is the knee-jerk reflex that occurs when a doctor taps your knee with a hammer, causing your leg to kick without you consciously or emotionally deciding to do so.

- Low Road Response: This term is often used in the context of emotional and cognitive processes. The “low road” refers to the rapid, automatic, and subconscious processing of stimuli. For example, when you perceive a threat, your brain might initiate a low road response that triggers the fight-or-flight reaction, releasing stress hormones and preparing your body to respond quickly without conscious thought.

While both low road responses and reflexive responses share the characteristic of quick, automatic reactions, there are differences in their underlying mechanisms and the types of stimuli they respond to. Low road responses are often more complex and can involve emotional and cognitive processing, whereas reflexive responses are usually simple, stereotypical actions triggered by a specific sensory input. In reflexive responses, such as the knee-jerk reflex, the amygdala is not typically immediately involved. Reflexes are primarily controlled by lower-level neural circuits in the spinal cord or brainstem. These reflex arcs are hardwired and do not directly involve conscious thought or higher-level brain regions like the amygdala and consequential emotions.

Therefore we have to distinguish emotions from reflexes. According to Lazarus (1991, p. 53): “Startle is a good example of the distinction between reflexes and emotions. Some writers have treated startle as a primitive emotion. I believe this is a mistake, because it confuses emotion with reflexes. Startle is relatively fixed and rigid and is best regarded as a sensorimotor reflex” (Lazarus, 1991, p.53). According to this view emotions are complex interactions.

- The high road response on the other hand is much slower than the reflexive road response and the low road response. This pathway allows for more complex, nuanced and reflective understanding of the stimulus and can lead to a more controlled and reasoned emotional response.

The (unconscious) mechanism leading to which road taken

All things simplified, the reflexive response can be considered as an automatic response, the low road response can be considered as an emotional response and the high road response can be consider as a reflective and reasoned response. This does not mean that a certain stimuli will only follow one particular path. It is likely that multiple paths can be followed and interact in more or less the same time. However that depend on the urgency of stimuli and is decided by the thalamus. In our view, the reflexive response is least interesting in the investigation of human behavior patterns. Therefore, we focus primarily on the distinction between low road response and the high road response.

A closer look into the origins of behavior

Diving deeper into the origins of human behavior beyond the abstract ‘nature’ and ‘nurture’ concepts often result in behaviors which are not strictly just sub-divisions of these two but are rather a mixture of ‘nature’ as well as ‘nurture’. Human behavior is influenced by a complex interplay of various determinants, including biological, psychological, social, cultural, and environmental factors. Understanding these determinants can help to gain insights into why people behave the way they do. Here are some of the key determinants of human behavior:

Biological Factors:

- Genetics: Genetic predispositions can influence personality traits, tendencies toward certain behaviors, and susceptibility to certain mental health conditions.

- Neurochemistry: Brain chemistry, including neurotransmitters and hormones, can impact mood, motivation, and behavior.

- Brain Structure: The physical structure of the brain and its regions can affect cognitive processes and behavior.

Psychological Factors:

- Cognition: How individuals think, perceive, and process information plays a crucial role in shaping behavior.

- Emotions: Emotional states can drive behavior, influence decision-making, and impact interpersonal interactions.

- Personality: Individual differences in personality traits, such as extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness, can influence behavior.

Social and Cultural Factors:

- Social Norms: Cultural and societal expectations and norms dictate acceptable behavior within a given community or group.

- Socialization: The process of learning and adopting behavior patterns, values, and beliefs from one’s culture, family, and peers.

- Social Influence: Pressure from others, conformity, and peer influence can affect behavior choices.

Environmental Factors:

- Physical Environment: The physical surroundings, including access to resources, can influence behavior. For example, access to healthy food choices can impact eating habits.

- Economic Factors: Socioeconomic status, income, and economic opportunities can affect lifestyle choices and behavior.

- Educational Opportunities: Access to education and the quality of education can influence knowledge and behavior.

Historical and Contextual Factors:

- Historical Events: Past events and historical context can shape societal attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors.

- Crisis Situations: Emergency situations, such as natural disasters or pandemics, can lead to changes in behavior.

- Media and Technology: Mass media, social media, and technology play a significant role in shaping opinions and behaviors.

Personal Values and Beliefs:

- Religion and Spirituality: Religious beliefs and practices can influence behavior and decision-making.

- Ethical and Moral Values: Personal values and moral principles can guide behavior choices.

Motivation and Incentives:

- Motivation: Internal and external factors, such as rewards, goals, and desires, can drive behavior.

- Incentives: The prospect of rewards or consequences can influence decision-making and behavior.

Health and Well-being:

- Physical Health: Physical health status, including chronic illnesses, can affect behavior.

- Mental Health: Mental health conditions, such as depression or anxiety, can influence emotions and behavior.

It’s important to note that these determinants are interconnected, and individual behavior is often the result of a complex interplay among them. Moreover, the relative importance of these determinants can vary greatly from person to person and across different situations. Understanding these factors can help us better comprehend and predict human behavior, but it is still a challenging and evolving field of study.

Experience

- First time experience

- Childhood exprience

- Learning (repetitive practicing)

- Learning from others

- Memory

- Belief formation

- Limiting beliefs

- Religion

- Skill formation

Learning

Learning is an interplay between experience and consciousness. Conscious thought is more energy consuming than unconscious thought.

With learning new skills by humans, there is relation between the level of consciousness and competence. The “Five Levels of Learning” model outlines the stages from ignorance to mastery. Initially, in unconscious incompetence, we are unaware of our lack of skill. As we become aware of this gap, we enter conscious incompetence, where we recognize our need to improve. Through practice, we reach conscious competence, where we can perform the skill but with deliberate effort. With continued repetition, we achieve unconscious competence, where the skill becomes second nature, performed effortlessly without conscious thought. Finally, conscious unconscious competence achieved when the skill can be explained to to others effortlessly without conscious thought.

How the road is taken

The “high road” and “low road” are terms often used to describe two different pathways in the brain involved in the processing of emotional and sensory stimuli, particularly in the context of fear or threat detection. These pathways are part of the broader system responsible for the brain’s response to stimuli, particularly those related to survival and emotional processing. Here’s an overview of how the determination is made between these pathways:

- High Road (Cortical Pathway):

- The high road involves the cortical pathway, which primarily includes the neocortex, particularly the prefrontal cortex, and other higher-order brain regions.

- When you receive a sensory stimulus, such as a sight or sound, it first enters the thalamus, which acts as a relay station.

- From the thalamus, the stimulus can take the high road, where it is directed to the cortex for more detailed and conscious processing.

- In the cortex, the stimulus is evaluated, analyzed, and interpreted in a way that is context-dependent and influenced by past experiences, memories, and cognitive processes.

- This pathway allows for more complex and nuanced understanding of the stimulus and can lead to a more controlled and reasoned emotional response.

- Low Road (Subcortical Pathway):

- The low road involves subcortical structures, primarily the amygdala and related brain regions.

- When a stimulus is perceived, it can also take the low road, bypassing the cortex to reach the amygdala directly.

- The amygdala is involved in rapid, automatic, and unconscious processing of emotional and threat-related stimuli.

- It triggers a quick, instinctive emotional response, such as fear or anxiety, without the need for conscious thought or analysis.

- This pathway is essential for immediate reactions to potential threats and is often associated with the fight-or-flight response.

The determination of whether the high road or low road is taken depends on several factors, including the nature of the stimulus, its intensity, the individual’s past experiences, and their current emotional state. Here are some key considerations:

- Stimulus Type: Some stimuli may directly activate the low road because they are perceived as potential threats (e.g., a sudden loud noise). Others may take the high road if they are less threatening or require more detailed analysis (e.g., a complex social interaction).

- Intensity: Intense or highly salient stimuli are more likely to activate the low road and trigger a rapid emotional response.

- Experience and Learning: Past experiences and conditioning can influence which pathway is taken. If an individual has learned to associate a particular stimulus with a threat, the low road may be more easily activated.

- Context: The context in which a stimulus is presented can also determine the pathway. In some situations, a stimulus may initially activate the low road, but subsequent cognitive processing in the cortex can modify the emotional response.

In summary, the brain determines whether the high road or low road is taken when receiving a stimulus based on a complex interplay of factors, including the nature of the stimulus, its intensity, past experiences, and the individual’s current cognitive and emotional state. These pathways work together to provide a balanced and adaptive response to the environment.

Low road alternative explanations

The idea behind the low road is “to take no chances.” If the front door to your home is suddenly knocking against the frame, it could be the wind. It could also be a burglar trying to get in. It’s far less dangerous to assume it’s a burglar and have it turn out to be the wind than to assume it’s the wind and have it turn out to be a burglar. The low road shoots first and asks questions later.

Difference low road and reflexive response

A “low road response” and a “reflexive response” are not exactly the same, but they share similarities in terms of their quick and automatic nature.

- Low Road Response: This term is often used in the context of emotional and cognitive processes. The “low road” refers to the rapid, automatic, and subconscious processing of stimuli. For example, when you perceive a threat, your brain might initiate a low road response that triggers the fight-or-flight reaction, releasing stress hormones and preparing your body to respond quickly without conscious thought.

- Reflexive Response: Reflexes are rapid, involuntary responses to a specific stimulus. They are typically controlled by the spinal cord or lower brain centers, bypassing conscious thought. For example, the knee-jerk reflex occurs when a doctor taps your knee with a hammer, causing your leg to kick without you consciously deciding to do so.

While both low road responses and reflexive responses share the characteristic of quick, automatic reactions, there are differences in their underlying mechanisms and the types of stimuli they respond to. Low road responses are often more complex and can involve emotional and cognitive processing, whereas reflexive responses are usually simple, stereotypical actions triggered by a specific sensory input.

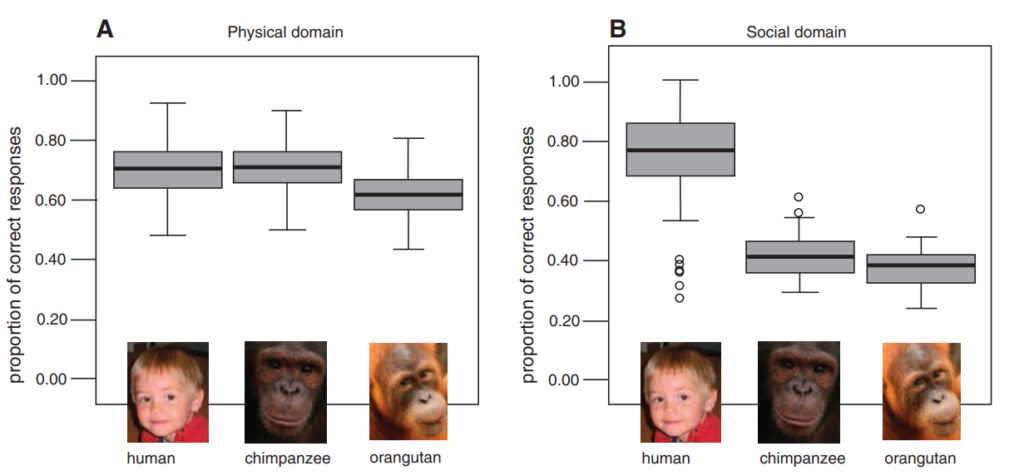

Human social behavior is the distinguishing characteristic compared to other species

The causes of the current human dominance in the realm of species are remarkable. Homo Sapiens Sapiens has not really physically evolved compared to say 50,000 years ago, when it did not have a dominant place in the hierarchy of species at all. Moreover, in the physical domain standalone behavior of 2.5 year old children (before literacy and schooling) does not give much cognitive difference compared to chimpanzees and orangutans. However, the real difference were humans stand out is in the social domain as shown in Display 5.

Therefore, to model human behavior patterns it is crucial to do so in a social or multi agent setting as we will attempt with Multi Agent Reinforcement Learning (MARL). In our view this paradigm is the most suitable of all current known Artificial Intelligence approaches to model human behavior patterns.